About a week ago, my good friend Rem Tanauan, a great poet himself whose work has profoundly influenced my own creative life, sent me this article that features an interview with Billy Collins, dubbed “the most popular poet in America”.

Rem and I are fans of his poems because they are conversational, witty, humorous, and down-to-earth. These are the kind of poems we want to see more of and some of our poems were definitely influenced by Billy Collin’s voice.

Rem asked me to share with him my thoughts on the article. What resulted was a brain dump of my ideas on building a new culture and community of poets in the Philippines.

I thought I would share them with you today. Poetry is the most freeing art form I know and discovering it had a profound effect on my mental health and quality of life. It is a great complement to the equally important work I do in philosophy.

In this post, I’ll be sharing my thoughts on several quotes from the article.

Enjoy.

You Are the Ultimate Judge of Your Work

I’ll start with this quote from the article:

I say, Get rid of it. Because if it got into a later poem it would be Scotch-taped on. It would not be part of the organic, you know, chi, the spine that the poem has, the way it all should be one continuous movement. Poems that lack that seem very mechanically put together, like a piece here and a part there.

The context of this quote is that Billy Collins is advocating that poems be written in one sitting. He writes them in 20-40 minutes and only returns to them after a few weeks to do some minor edits. According to him, writing poems in one sitting creates a more organic poem that has “one continuous movement”. This, he said, is more desirable than poems that are “mechanically put together.”

While I sympathize with his advice, and I do write poems in one sitting, I have some reservations for what he said here partly because I do blackout poetry and by their nature blackout poems are scotch-taped poems. Their mechanical nature is what makes them different. The reason why I like them is that I don’t have to stress a lot about being original when I do them. I might experience some stress when looking for patterns between words, but at least I am taking a rest from the stress of trying to be original all the time.

Of course, it isn’t impossible for a blackout poem to suddenly emerge like a typical poem, which has the characteristic of having “one continuous movement” (what he describes here as “chi”). However, what if a poem doesn’t have this? Is it a bad poem? Was my process for coming up with it a wrong way of doing poetry even if I enjoyed doing the process?

These questions led me to think about how we actually judge a poem. We can criticize a poem by not having this element of chi but isn’t our criticism of that poem subjective, based on our biases and tastes? Heck, aren’t all our judgments of art subjective?

One reason why I think this is an important question to answer is that I actually believe (and I share this with Rem and most of our poet friends) that poetry, or any other art for that matter, should ONLY be done with the purpose of enriching our quality of lives, not to diminish joy or the feeling of “ginhawa” (a Filipino concept of integral well-being, which I’ll loosely translate here into “bliss”) that is inherent in all creative pursuits. Now, what if a poet wrote a mechanical poem but did so “blissfully”? Do we say that his work is not good just because it was mechanical? Whose standards are we using to judge the work?

This made me think that, perhaps, by describing how writing poetry happens, we are actually prescribing a “right way” to write poetry. If so, how different would we be from formalists who have tried to proselytize “one way” of doing poetry?

Ultimately, I asked myself, “If blissful writing is the organizing principle, who is the ultimate judge of a poet’s work?

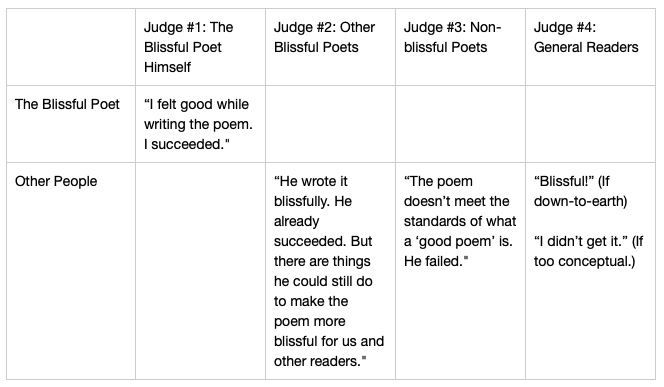

The way I see it, there are only two judges:

- The poet himself

- Other people (other poets who believe in writing blissfully, other poets who don’t share the value of blissful writing, and general readers)

I thought about how this judgment process happens and constructed the following table:

From this meditation, I realized that the ultimate judge of any poem is the poet him/herself. The reason for this is that any definition of success is always subjective first before it is objective. Any group can impose particular standards of what a good poem is that its members can agree on. But these standards are not necessarily the standards of an individual. So even if feedbacks are helpful, even if objective standards have their use in communities, a poet or an artist needs to trust his own standards first so he can trust his own abilities.

Any community of poets who would claim to be an alternative to business-as-usual should embrace this attitude. Though feedback is very much needed from fellow poets and the general audience, these should not replace the most important judge or feedback-giver of all: oneself. This is because if a poet does not learn how to trust himself, he won’t be able to produce any work. And according to Billy Collins, from the same article, the most important thing is that a poet writes.

Actually, I don’t think you can be really badly influenced by anyone, as long as it makes you write.

”Did You Feel Good While Writing?”

This brings me to my next meditation. As a thought experiment, imagine that a highly intellectual and conceptual formalist poet wanted to join the alternative community of blissful poets. She said she wanted to join because she liked the group’s emphasis on feeling joy throughout the creative process. By leaving the dog-eat-dog culture behind, she hopes to experience a different relationship with her writing. She immediately experiences what she is looking for because there are no strong standards or harsh judgments in the group.

However, here’s the problem: She still writes highly intellectual, highly formal, and highly conceptual poems that are not blissful for readers. When this was brought to her attention, she said this is the only way she knows how to write. This is the writing that makes her feel good. What will be the right response in this situation? Will the community of blissful poets banish her for failing to write more intuitive and down-to-earth poems? If this is the response that the community gives, is it still true to its principle of blissful creativity? Is it still facilitative, or is it already prescriptive?

For me, the answer is clear. For a poetry group to truly exemplify the principle of “ginhawa”, it should be a space where there are fewer and fewer constraints. To quote the Tao Te Ching here:

The more restrictions and prohibitions there are,

The poorer the people will be.

Lesser rules mean that there is more space for ALL kinds of poetry. Even the super formalist poems should be welcomed. Experimental poems should be welcomed (like blackouts). Intellectual poems should not be looked down on. This means that the alternative community of blissful poets becomes a space of true freedom. It does not prescribe strongly on anything. If there is any prescription, an organizing principle that binds everything, it is only this:

“Did you feel good while writing? Ok. That’s it.”

If you add on that, then you add constraints that could muddle the very essence of what “feeling good” is. The subjective blissful experience of an individual poet should be the ultimate principle.

Freedom in Poetry

The role of freedom in poetry was nicely said by Collins in this quote in the article:

I grew by allowing aspects of myself that I had previously excluded into the poetry. I think all poets—younger poets particularly—have a private sense of decorum, meaning they feel there are certain things they should write about and other things they shouldn’t.

My dream is for poetry to be freeing, and if a community should be a space for free poetry, it needs to evolve into that place where poets are free to explore the different parts of themselves, where no topic is out of the conversation and no form is out of experimentation. Of course, there are intricacies of this and we shouldn’t expect any community of poets to immediately be like this. But it’s a nice dream.

I also think that this should be one of the main goals of any critique of traditional poetry. To be truly an alternative way, alternative poetry has to be freeing. It should, as much as possible, prevent creating rules on what should be and what shouldn’t be explored. It would be nice to see that each poet of such a group is exploring their own topics and their own structures and there should be a venue for them in the community to show their work. They should be given the time to share during gatherings or they should be given a platform where they can share their discoveries. They should be given a voice and there shouldn’t be censorship at all.

A Solo Act

All of these ties well with the general subject of the tension between an individual’s need for community and his need for authenticity. Here is an interesting quote from the article that jumps into this:

For me poetry was always a solo act. A romantic idea maybe, but I thought that poetry was something you did in solitude, and the idea of sharing your work with anybody was completely antithetical to what I thought poetry was all about.

I think the challenge for any community of blissful poets is how it can be a place where camaraderie does not muddle with the solitude that poetry requires. How can poets be “alone together”? How can the community be a space where an individual’s need for community and the need for authenticity is both fulfilled?

Keep Your Center

In ending, I think I want to highlight again this tension between the poet as the Self and the poet as a member of a group. In the article, Billy Collins sees this tension:

The image one has to present as a performer, as an interviewee and whatnot, is a very different self from the sensibility that actually creates the poems. You need to keep your center, the part that writes the poems, and not spin off into popularity.

I have been meditating on this for a very long time. Every time I show up to the world, a part of me is lost. This is expected. But what I wish to have is a community, a space where the potential damages of sharing my work with others are lessened or minimized, a sort of creative insurance.

Building a new culture and community of poets in the Philippines who believe that creativity does not have to always be competitive and harsh is hard. Any such endeavor needs to prioritize the maintenance of a safe space where every individual member is an asset. What I shared above are my thoughts on how this might be done.

My friend Rem plans to reopen his poetry course and community of blissful poets, “Tungko ng Tula”, by January 2021. If you want to discover a different kind of poetry or just curious about anything I shared in this article, I encourage you to visit Rem’s IG page @ditomuna. Read his beautiful tanaga poems (four lines, seven syllables) and while you’re at it, send him a message.

The course and community also have a website at tungkongtula.com, which is currently only written in Filipino.